The Woman in Black: History

by Simon MurgatroydNote: This article concentrates on the creation, origin and history of the play as related to theatre in the round and Scarborough, where it originally premiered. It does not explore its wider success in the West End or globally.

The Woman in Black

Since the Stephen Joseph Theatre in thew Round first staged Stephen Mallatratt’s adaptation of Susan Hill’s novella The Woman In Black, it has become one of the most successful plays ever to be staged in the West End and has gone onto global recognition and success. Yet it all began as a low budget Christmas filler in Scarborough.

The Woman In Black was first published in 1983, an unexpected change of genre for the noted Scarborough born author Susan Hill which would draw praise and critical acclaim over the years for her version of the English ghost story.

In 1986, the late writer and actor Stephen Mallatratt read the ghost story whilst on holiday in Greece and was immediately taken by the piece.

“A Greek beach must be the most inappropriate place to read a story like this! But that was where I read it, and, like most people who have read it, I was very struck by it. It was a bit of a nutty idea, really. But when I got back I wrote to Susan Hill saying, either would she consider adapting it, or would she let me?”

Susan was not convinced by the idea but, in July 1986, she replied to Stephen in a letter still held in archive.

“I’m amazed that you should think it remotely possible to do the book on stage, but thinking of what has been done in dramatic form, which would seem pretty unlikely, I imagine there must be a way, if you think so!”

Citing part of the charm was that the play would be staged in her childhood home of Scarborough, she gave Stephen permission to adapt the play and in September 1986, the pair signed a contract giving Stephen the rights to adapt the play. At some point in the next twelve months, he adapted the play.

The result impressed Susan Hill, who had apparently practically forgotten about Stephen’s request from the previous year. She read the script and thought, “Good Lord, this man has actually done it... It’s very clever.”

That same year, the Artistic Director of the Stephen Joseph Theatre in the Round, Alan Ayckbourn, began a two year sabbatical at the National Theatre from 1986 to 1988. The day to day running of the theatre - including the programming - passed to Robin Herford. During the summer of 1987, he conceived the idea of a “Christmas Stocking filler” which would use the season’s remaining production budget for a seasonal ghost story staged in the 70 seat studio theatre.

Robin approached Stephen, the theatre’s resident writer, with the idea and, due to the limited budget, the proviso, “I can’t afford to have more than four actors or elaborate sets.” Stephen reminded him about his interest in The Woman In Black, which felt to Robin like a possible solution, albeit with one glaring issue.

“I read the book and was immediately impressed by its evocative power, but it had one drawback - a list of characters numbering about a dozen. Stephen seemed unperturbed, and proceeded to write me a two-handed play, which not only solved my budgetary problems but actually enhanced the original premise of Susan’s story.”

With the author’s approval and a script in place, Robin took on directing duties with design by Michael Holt, lighting by Mick Thomas and sound by Jackie Staines. The two acting roles were taken by Jon Strickland as Arthur Kipps and Dominic Letts as the Actor with Lesley Meade in an uncredited role.

For those unfamiliar with the play, Stephen’s masterstroke was to transfer the action of the play to a Victorian theatre, where a young lawyer is asked to partake in the retelling of a chilling story by The Actor, who plays all the other roles. In a single stroke, Stephen had negated the staging problems of the novella, as locations - be it London or a causeway through the marshes - and characters were left to the skill of the actors, a hugely memorable sound plot and one other essential element noted by Robin: “It is the magic of theatre, made possible only by that most precious and under-used of commodities, the audience’s imagination.”

Another stroke of inspiration came with how to handle the ghost itself. As anyone who has seen The Woman in Black will know, the play is haunted by a third character. From the word go, it was felt it important to not spoil the surprise but how to do this whilst not breaking the acting union Equity's rules for crediting everyone involved within a production? Robin's clever solution was to hide the credit in plain sight in the programme; a solution adapted for and still used to this day in productions of the play.

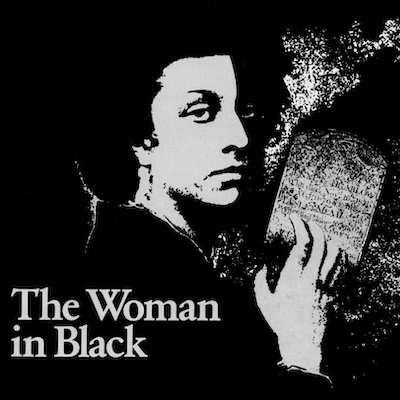

There was also another clever credit in the production's poster, which features the woman in black and a gravestone. By peering at the gravestone, the name Jennet Drablow - which should have read Jennet Humfrye but for a mistake in the original manuscript only spotted later - can be made out. Beneath it, unnoticed by most people, it is possible to make out the name 'Lesley Mead' [sic] - an actor with the Scarborough company. The poster can be found on the Images page.

Although a great deal of credit must go to Mallatratt for his adaption and Herford for his direction, the production was also gifted with a memorable sound-plot designed by Jackie Staines, which was recreated for the original West End production and used for many years. She would utilise Robin's wife, the late actress Lesley Meade, for the narration of the letters discovered during the play and his son, Olivier, for the scream of a young boy for which he was paid £10.

The most memorable part of the sound design though is also something which held a surprise until 2021. One of the given 'facts' regarding The Woman in Black is the lack of involvement of Alan Ayckbourn. He was on his sabbatical at the National Theatre and thus wasn't part of the team which produced the play in Scarborough. However, in an interview with his archivist in 2022, he revealed he did play an uncredited part in its creation.

During the '70 & '80s, Alan was responsible for creating the sound designs and plots for many of the productions at the Stephen Joseph Theatre in the Round and he had a state-of-the-art recording facility at his home, far superior to anything in the actual theatre. When it came to recording the famed Nine Lives Causeway scene for The Woman in Black with the sound of the horse & cart crashing off the causeway, Alan recalls Robin Herford asked him for help as they weren't able to technically achieve the effect. As a result, Alan created and recorded the original seminal effect from the show - although he asked to remain uncredited for the work given Jackie Staines' otherwise unforgettable sound design.

The Woman In Black opened on Friday 11 December 1987 in the studio at the Stephen Joseph Theatre in the Round in what Robin later described as “a rough and ready” production. Both he and Stephen were unsure of whether it would work or not; a feeling Stephen still felt at the end of the first night.

“There was good solid applause at the end, and our friends said all the right things - they would, wouldn’t they? - but then we were left in a dark room with about eighty odd chairs, a lot of black cloth and a fair bit of doubt.”

The first reviews appeared on the Monday and did not offer much more clarification. The Daily Telegraph reviewer was the most enthusiastic noting the play “put the wind up its audience” and himself. The Scarborough Evening News’ reviewer had the somewhat unpleasant feeling of “the skin on the back of my neck positively crawling up onto my skull.” While The Guardian was unimpressed citing a failure “to generate any tension”, although this from a reviewer who couldn’t be bothered to proof his spieling of the writer Stephen Mallatratt, referring to him as Mallatrapp!

Critics were not going to make or break this play though. Its success was always going to be dependent on word of mouth. For one significant person, it ticked every box. Susan Hill, visiting Scarborough for only the second time in thirty years, recalled in 2008 that there, “on the first of many, many occasions, I was riveted by the play.”

She was not the only one to enjoy it. Audiences fell in love with the show, so much so that Stephen recalled the theatre could barely cope with demand.

“The next day [after the reviews] something happened that you always hope will, and so seldom does. The box office phones started to ring and queues began to form. By the end of the short run we’d squeezed in extra chairs for every performance and we’d added three or four late night performances, selling out every time.”

The play ran for just three weeks, but it had been successful far beyond anyone could ever have imagined or hoped. Susan Hill fondly recalls Alan Ayckbourn telling her that there were now two great plays adapted from ghost stories, The Turn of The Screw and The Woman In Black.

With no expectations behind it, The Woman In Black proved to be an extraordinary success in Scarborough. Although that would merely be the start of a remarkable journey.

In January 1989, it transferred to London, eventually finding a permanent home at the Fortune Theatre where, in June 2011, it played its 9000th performance and, in 2019, it celebrated its 30th anniversary in the West End. Sadly, in November 2022, it was announced the play would close in March 2023 having become the second most performed West End play after Agatha Christie's The Mousetrap.

It is estimated the play has been seen by more than 7 million people in the UK alone since 1987 and it has been produced in more than 40 other countries around the world.

Unfortunately, this success did not feed back into the Stephen Joseph Theatre in the Round which, ordinarily, would have expected to reap the benefits and - more significantly - financial remuneration though royalties. Normally, a production contract includes a standard clause for a theatre to be remunerated if the play opens in London. However, this did not happen for reasons still unclear to this day. Certainly the original contract held in archive solely between Susan Hill and Stephen Mallatratt states all royalties be split equally between author and adaptor, but there is no believed surviving copy of the contact with the theatre to explain why it did not include remuneration clauses. This will probably forever remain a mystery and the only revenue the theatre saw was, according to Alan Ayckbourn's biographer Paul Allen, 'limited to a percentage of Stephen Mallatratt's royalties up to a grand total of £5,000."

Those connected with the play did benefit though, not least Robin Herford who Stephen Mallatratt insisted the contract include a clause that Robin had first refusal on directing future productions of the play. Ordinarily this would normally have been regarded as a nice gesture with no long term repercussions. Neither Stephen nor Robin realised how successful the play would be and Robin has been associated with it ever since. He directed the West End premiere and continued to redirect the company change every year until its closure in 2023. The play has taken him around the world directing productions from the United States to Japan. The designer Michael Holt has also frequently designed for revivals and the West End production of the play.

By its tenth anniversary in 1997, the play had become firmly established in London and an undisputed success. To mark the anniversary, the Stephen Joseph Theatre (opened as the company's first permanent home in 1996) was granted dispensation to stage a revival in the end-stage McCarthy auditorium; this was possibly to reflect the fact the theatre had never benefited from the original production.

Robin Herford returned to direct the revival with Michael Holt designing and Lesley Meade also returning. The company featured a company stalwart Peter Laird as Arthur Kipps and a relative newcomer in the role of the Actor. Having worked with him in Scarborough the previous year, Robin cast the little known Martin Freeman in the role; Martin would go on to become an extraordinarily successful actor on stage and screen from playing Bilbo Baggins in The Hobbit movies to Watson in the acclaimed BBC drama Sherlock.

In 2015, the Stephen Joseph Theatre celebrated its 60th anniversary and a decision was made to revive several classic premiered at the theatre: Alan Ayckbourn's Confusions, Tom Firth's Neville's Island and, naturally, The Woman in Black.

This production featured a world first for The Woman in Black with a father and son taking the roles of Arthur Kipps and the Actor - Christopher and Tom Godwin. Christopher had been a stalwart of Alan Ayckbourn's company in Scarborough during the 1970s and had created several of Alan's most famous characters - and Tom's birth had even been announced onstage by Alan! Robin again returned to direct the production which then transferred into London.

From humble beginnings, The Woman In Black has become an extraordinary phenomenon, scaring audiences around the world. It is this which Robin Herford believes is the key to that popularity and enduring appeal more than three decades later.

“It shows you can experience fear in a theatre, which so few people believe to be possible. It’s a cracking story that deals with the supernatural, but it is conceived in very human terms. The Woman In Black’s tragedy is a very human tragedy you can relate to. It is so clear and terrifying.”

"Come, you're not going to start telling me strange tales of lonely houses?"

Article by and copyright of Simon Murgatroyd, all rights reserved 2022. Please do not reproduce without permission of the copyright holder.